By Catie Crandell and Camey VanSant

Students registering for spring courses this week can choose from a wide variety of offerings exploring how digital and computational methods illuminate the humanities. Whether they just want to dip their toes or take the full plunge, this spring’s courses offer dozens of classes from departments and programs that range from Art and Archaeology to Latin American Studies.

For example, Sierra Eckert’s “Introduction to Digital Humanities: Slow Data” is designed to give students the opportunity to develop both practical skills (data set analysis and data visualization) as well as conceptual ones (project management and collaboration) (see a draft of the course syllabus). Ultimately, in making students more familiar with objects like charts and graphs, the course will make students “better readers” and interpreters of the layers of mediation and interpretation that shape data and arguments made with data.

Eckert, Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Center for Digital Humanities and a Perkins Fellow at the Humanities Council, wants to dispense with the misconception that digital methods and tools are “a radical break from traditional methods of literary study.” Instead, she sees them as tools “well suited for tracing questions about cultural transmission over a long durée, or challenge traditional categories of periodization, national or linguistic tradition.”

This course will introduce undergraduates to key debates around the intersection of computational methods and humanities research questions while also providing an entirely new way of thinking about Digital Humanities. “We tend to think of information or digital media as fast, ethereal, near-limitless,” Eckert pointed out, “But there are a number of ways that data can be thought of as something consumed in real space in time: we see this in the amount of electricity that it takes to run a databank, or the hours of labor taken to digitize facsimiles of books, or the designing of electronic circuitry.”

A graduate seminar taught by Meredith Martin and Rebecca Munson, “Literature, Data, Interpretation”, takes up similar questions to those asked by Eckert: “How and why has literary criticism relied on or resisted quantitative methods?” (see a draft of the course syllabus)

“We think of quantification not only as “counting” but as the broader question of “what counts” as an object worth studying, and why?” explained Meredith Martin, Associate Professor of English and Faculty Director of the Center for Digital Humanities. As such, “the course will cover disciplinary histories, classification, how sources become objects of study, and how institutions and archives might provide or prevent access to particular kinds of questions.”

“We’re hoping to humanize the various ways students are already implicated and participating in data management on several scales. Students will leave the course with an understanding of how to incorporate quantitative methods, should they choose to, in responsible and equitable ways.”

As co-teacher Rebecca Munson, Project and Education Coordinator for the Center for Digital Humanities, explained: “We’ll be using the history of quantification to encourage students to trouble existing categories and to be self-reflexive in their criticism. We hope the course enables students to identify and articulate the challenges of interdisciplinary and intersectional scholarship in their home fields, and to consider how their scholarship will fit in with and potentially improve their disciplines in the future.”

Digital humanities tools and methods also figure prominently in several other humanities courses. For instance, Esther Schor, Leonard L. Milberg ’53 Professor of American Jewish Studies and Professor of English, said she created her new course, “Multicultural London: The Literature of Migrants and Immigrants”, as a “‘virtual London’ experience for students prevented from studying abroad next spring.”

The course combines readings by authors like Virginia Woolf, Zadie Smith, and Monica Ali with instruction in digital tools, including mapping and annotation. Students will apply these tools to curate their research project: an online archive.

“I’ve designed this course on London’s vibrant immigrant culture to be as immersive as possible,” Schor explained. “Students will develop research projects collaboratively in an ongoing, cumulative course blog, and at the same time compile and reflect on an original archive of documents and images on a topic of their choosing.”

Schor is assembling a lineup of guests who will join the virtual conversation on course readings and offer insight on migration-related issues. On the list of topics? “The history of migration, changing neighborhoods, community newspapers, refugees seeking asylum, multilingualism, theatre by and about immigrants, foodways, and public art,” Schor said.

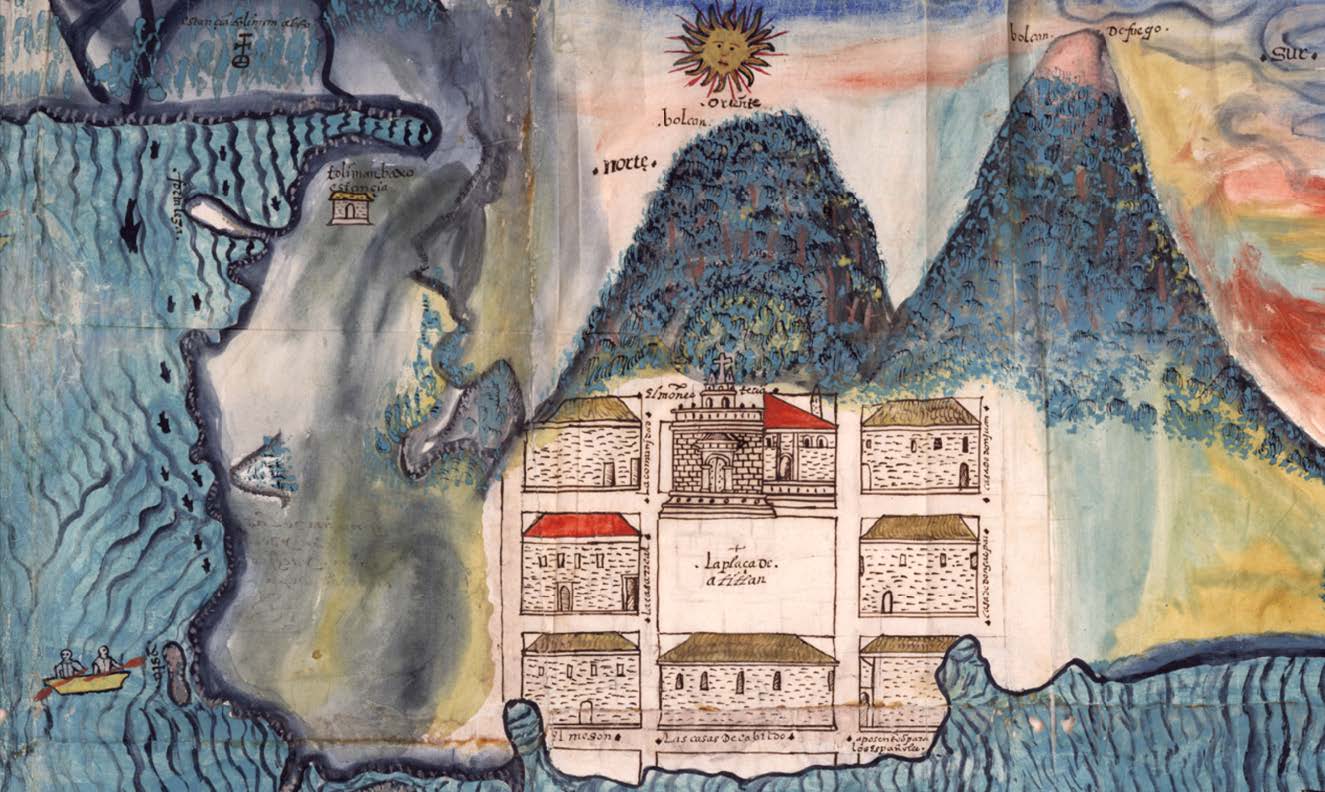

Mapping of historical landscapes also lies at the heart Noa Corcoran-Tadd’s “Reading the Landscapes of Colonial Latin America”. Corcoran-Tadd, Associate Research Scholar and Lecturer in Latin American Studies, aims to capture the “places, territories, and ecologies” of colonialism in Latin America between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. Borrowing methods from history, geography, archaeology, and art history, the course will harness digital tools to visualize the “complexities and legacies” of the colonial period.

Students in the course will complete three digital projects across the semester: one mapping individual travelers’ itineraries in the 15th and 16th century, one examining digitized maps of colonial Mexico from Princeton’s collections, and one interpreting contemporary satellite imagery to trace the impacts of the last five hundred years.

“While we often see ‘landscape’ used in its many figurative senses,” explained Corcoran-Tadd, “the course takes the notion of landscape in a very literal and material sense to look at the remaking and representation” that are always a part of cartography.

For students in Melissa Reynolds’s spring course, the digital will be both topic and method.

“A History of Words: Technologies of Communication from Cuneiform to Coding” comprises a weekly asynchronous lecture and synchronous discussion on how phenomena like the invention of the printing press and the rise of newspapers changed history. Complementing these components will be a weekly “digital lab.”

“Every week, students will visit a digital project that presents the communications technology we’ve studied that week in our lecture and discussion,” explained Reynolds, Perkins-Cotsen Postdoctoral Fellow in the Society of Fellows and Lecturer in the Council of the Humanities. Students will then “try their hand at a digital skill set that replicates in some way a strategy used within these established digital archives or editions,” such as mapping or text encoding.

“Students should understand that every communications technology has particular limitations or structures that shape not just what we know but how we know it,” Reynolds said. “Having a better grasp on how it is that we know what we know today—largely through digital media—is absolutely critical to students’ development into the thinkers and leaders our contemporary society needs.”

Identifying and developing courses at the intersection of the humanities and computer science is crucial to the work of the Humanities Computing Curriculum Committee (HC3), formed last academic year.

Comprising faculty and administrators, HC3 aims to provide opportunities for STEM concentrators to attend to the ethical and societal impacts of their work and for humanities students to develop digital skills and competencies.

HC3 also plans events, community partnership, and workshops promoting digital equity.

The Certificate in Humanistic Studies promotes this kind of interdisciplinary inquiry, as well. Students in the certificate program can elect to build their junior and senior curricula to explore digital approaches to the humanities.

As Reynolds says about her course, “At the end of the day, education in digital methodologies is humanities education.”